We f*** love crystal. ✧*。ヾ(。>﹏<。)ノ゙✧*。 💉

One thing that’s quite amazing about the crystal language is how it does away with quite a lot of unnecessary null/type safety checks, instead implementing these things directly into the compiler. You have all this at the cost of… basically no performance loss or type safety whatsoever. It’s quite an incredible feat honestly.

While this (alongside its incredible C static library linking) has made it amazing for systems programming, and suitable for a plethora of performance-intensive tasks, it has come with one major drawback - the --release flag.

More specifically, just how bloody slow it is to compile - this issue hasn’t gone by the devs, who have been discussing the implementation of incremental compilation for 3 years. Their most recent public conversation (and the most informative) was in a GitHub thread before the 1.0 release back in 2020.

And honestly, reading the rest of the crystal community coping with this is just too funny.

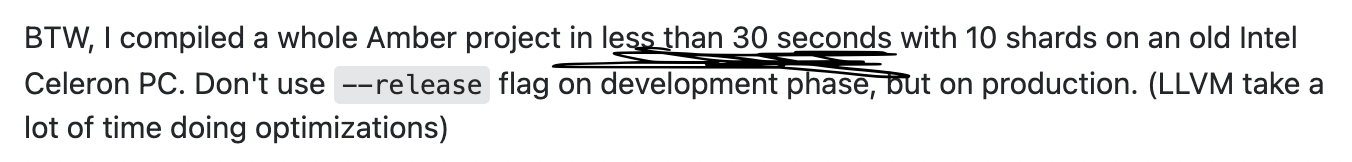

“30 seconds is a decent compile time actually” - statements dreamed up by the utterly deranged

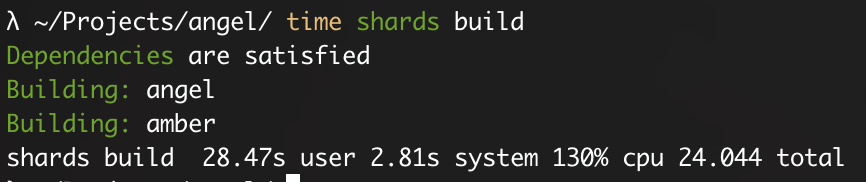

During our research for this writeup, one thing that stood out is that when building a full amber project on an M1 MacBook, we achieved almost identical results to one of the commenters in the thread: specifically they had an Intel Celeron® 2957U @ 1.40GHz.

It’s almost like the compiler isn’t actually dependent on CPU performance at all~ but, it should be, right? How are you supposed to reasonably build larger crystal projects at this rate?

Well, the short answer is, you kinda just suffer. It’s already been answered in a GitHub thread.

The fact that there’s absolutely 0 difference in performance is probably indicative that there is something fundamentally going wrong with how the compiler works though, and we’re curious. Let’s take a deeper look.

Into hell we go

Shamelessly taken from this Stack Overflow response,

In long, there are four main phases within the Crystal compiler:

- Type-checking and macro expansion

- Code generation to LLVM

- Optimization (by LLVM)

- Binary generation (by LLVM)

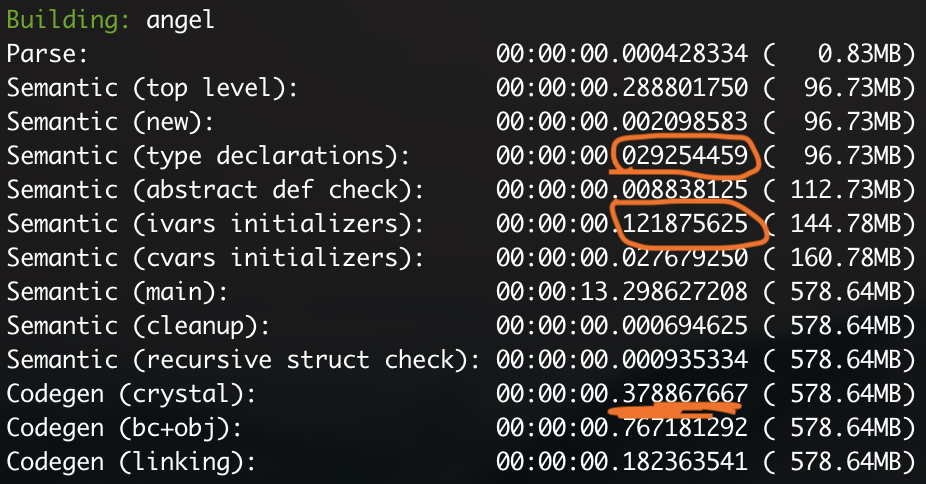

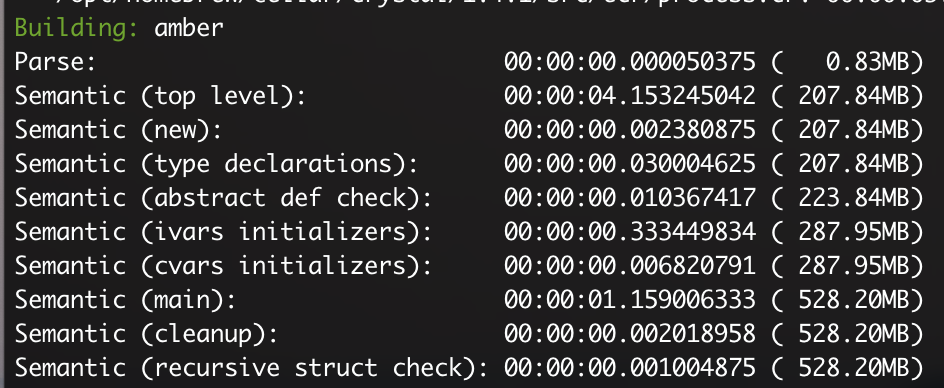

We can start by breaking down what the compiler is doing at each stage - let’s revisit the amber project once more, since it’s the best benchmark with many different files & shards.

Ah. So it looks like it’s the code generation that takes the most time. We can confirm this if we run the command again while running the --no-codegen flag.

shards build -s --no-codegen 17.63s user 1.62s system 98% cpu 19.505 totalSo, we found the culprit. Nice.

Though, this is where we run into a bit of a problem, and where our opinion on writing this becomes completely invalid (mainly because we have never read a book about compilers) - when you pass code generation through to the compiler, it starts to become less & less dependent on how much code you can compile & link together, and more-so what your code generation algorithm consists of. But why?

Code generation algorithms

The idea behind code generation isn’t simply just the production of some lower level machine/assembly code, but also the application of low-level optimizations, while retaining the exact same message & output of the original intended program, while remaining as efficient on hardware resources as possible. These optimizations can be as something as smol as removing needless variable assignments - i.e:

def add_some(n)

x, y = 4, 3

z = n + (y + x)

z

end

# => becomes...

def add_some(n)

n + 7

end…to lower level bit manipulation & shifting to achieve algorithmic simplicity & speedups, which would take too long to write out & explain so we’ll refrain from doing so.

One of the ways this is achieved is through peephole optimization, which is a whole nightmare that wikipedia very confusingly explains.

The idea behind it is to offhand the calculation of as many assigned variables at compile time as possible (not to be confused with the likes of constexpr (in C++), the deletion of null sequences - i.e, code that achieves no purpose to the effect of the whole program, and the combination of operations.

Just as a quick example, this is really easily done with something like;

def is_even(x)

x % 2 == 0

end

# => becomes...

def is_even(x)

(x & 1) == 1

endFrom our research, we have gathered the Crystal compiler heavily suffers from two main issues: the target platform of the generator, and its evaluation order.

As usual, there was an extremely good GitHub thread that goes into a lot of detail about this, but for the impatient (and because we’re not smart enough to talk about compiler design) we’ll do our best to bring some more detail, and explain the issue as best as we can.

Crystal has largely solved the issue of slow compile times - in terms of type inference, by requiring (polymorphic) functions to have a strict annotated return type, though the compiler cannot fully utilize this information provided by the type restriction - it can only see that the function must return its annotated type, and cannot make further assumptions about how that function will be used in the wider context of the program.

However, what we shouldn’t do is enforce that such type restrictions exist. It makes the language much less flexible, and in my view is entirely unnecessary. If the public API of a logical “module” of code is annotated with type restrictions (and it doesn’t even need to be 100% coverage, only 90%), we still vastly reduce the number of possible method instantiations on the external API. This in turn vastly reduces the possible number of ways internal methods without any type restrictions are instantiated. - RX14 ♥️

Having the compiler mainly rely on caching is more of a band-aid than a workaround, and >inb4 just make it multithreaded already lol

Sure, but you still have to deal with processing all those message queues to actually get the benefit of having a multithreaded compiler. Without proper Futures or async capability (similar to that of Rust’s) you won’t feel much of a benefit from multithreading if your compiler isn’t smart enough to understand wider contexts in your program exists to be able to compile code ahead of the main thread in the first place.

This is sadly much of the issue with LLVM’s iffiness with handling blocks of sequential data when you’re not writing native LLVM.

Edit: we tried reading through the LLVM docs to understand non-native support better but please feel free to read through yourself

The Crystal compiler needs closer interlop with native LLVM, but sadly this isn’t the issue with the developers, but rather the architecture of LLVM which does not fully agree with Crystal’s newer ideas on type exceptions, strong typing & annotation.

Though these issues can and will be ironed out (we’ll be praying for you Crystal team!! 🥳) it will be a ways off before it’s more ready to use in larger codebases.

In conclusion

Tl;DR, code generation in languages not native to your compiler toolchain is a nightmare, if you think you can do it better, make a PR, have fun ferreting dead/weak code in your compiler output for weeks on end trying to speed up the process, implement all the multithreading you want - the toolchain hungers.

Thanks for coming to our ted talk.

Backlinks

No backlinks found.

Go back